Zuber and Dufour were the two largest and oldest manufacturers and their papers were more varied and of better quality than those of their rivals. Dufour set up first in Macon, but in 1807 he established himself in Paris at 10 Rue Beauvau. He began his career by making drapery papers, dividing the walls of a room into long narrow vertical panels of paper imitating folds of silk separated by lances, garlands or architectural ornaments. Drapery paper had only a short vogue however, and Dufour soon turned to scenic papers which offered a greater variety of subject. The first scenic paper which he produced while still living in Macon was Sauvage de la Mer Pacifique, *composed upon discoveries made by Captain Cook, La Pérouse and other travellers* which appeared in 1805; but his best known work dates from after 1814 when perhaps the end of the Napoleonic War made marketing and distribution less difficult. The subjects are about equally divided between mythological scenes like La Galerie Mythologique or the famous Cupid and Psyche series, subjects from history, panoramic views of wetl-known cities such as London, Paris or Lyon, or more general views of idealised landscapes. One of the most popular of the latter class was Le Petit Décor. Unlike the majority of Dufour’s productions this paper is not securely dated, but it almost certainly made its first appearance circa 1815. The costumes of the small figures support such a date. In 1830 a new edition of the paper was brought out in which the costumes were altered to the style of the day. The manufacture of the printing blocks was a laborious process and it was not uncommon to re-use existing blocks for a new paper. The blocks of the Petit Décor were used in this way to make the background for the series known as Le Cid in which Spanish scenes and figures replace the French.

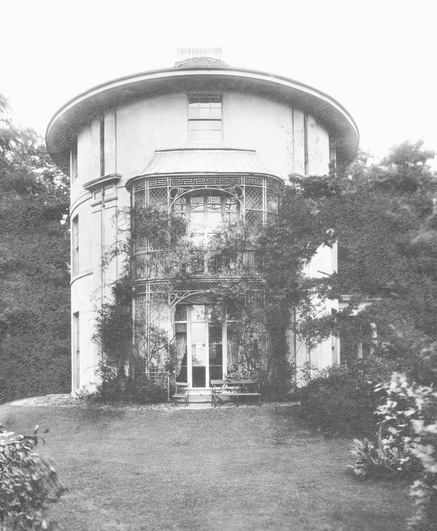

The Havering paper is an example of the first state of the design and probably the only such example in the country. By the 1970’s it was in a sorry condition but still had considerable charm. The colours were bright, where they had not peeled off and one could gain an impression of what such rooms were originally like; the total effect was re-inforced by the ceiling painted to resemble clouds and the dado which was covered with painted illusionist panelling. It is probably worthwhile to give a brief account of the method by which such decorations were manufactured. All very early papers were printed on small sheets of paper ( roughly 20″ x 20′ ) pasted together to form strips of the requisite length. Although continuous rolls were made from 1800 onwards some of the papers of later date were still printed on strips composed of small sheets. Paper was an expensive commodity and presumably the manufacturers were unwilling to waste their existing stocks. The glue-impregnated paper was prepared with an earth-coloured ground and size and it was then ready for the printer. Wooden blocks were used like those employed today for the production of hand-blocked linen and it was necessary to have as many different blocks as there were colours or shades. One colour was printed at a time and left to dry before proceeding with another. Tempera colours mixed with hot glue were used for the printing. The durability of the papers was a direct result of the high quality of the materials used. Almost all the paper was made from pure linen rags and was more resistant to the attack of moderate damp than any modern production. The fashion for panoramic papers tailed off after 1820, and by 1840 they were seldom used. There are very few examples of this kind of decoration still surviving in England, and The Round House paper is a valuable relic, although it was in the 1970’s past the possibility of economic repair. It was probably put up in the1820s, that is about five years after its first appearance in Paris, but nothing is known of the Whitehurst family which could make a more precise dating possible. Before restoration of the house, the paper was removed carefully and taken to the Passmore Edwards Museum to be stored under controlled conditions until restoration could be undertaken. A part, only, of the dado remains. Information is also lacking about the other alterations made to the interior of the building. Some of the principle rooms have fire-surrounds and plaster cornices which appear to date from 1870 and it is possible that the curiously large doors with their massive reeded architraves are part of the same scheme of improvement. In 1930 an exact survey of the building was made by the architect W. G. Newton, the son of Ernest Newton, in connection with the installation of a system of central heating and it was under Newton’s direction that the position of the basement stair was changed to its present location at the base of the main stair. It had previously been in the lobby to the left of the main entrance. After the death of the Reverend Joseph Pemberton and his sister, the house was briefly tenanted before being requisitioned during the 1940-5 period. It was used by the army for the holding of its own miscreants and as a store for furniture from bombed homes. Unfortunately the placing of sandbags around the house encouraged the penetration of damp leading to severe wet and dry rot and wood worm infestation. The house, now in a bad state of repair, was acquired in 1952 together with its surrounding land by E.M.Heap, then living at The Hall. Shortly after, he arranged the removal of the diseased timbers, treated those remaining and made the house again weatherproof. Although remaining inhabitable following this holding operation it did not substantially decay further.

His son Michael was given the house in 1977 and together with his wife Mary-Anne determined to restore it as their home. Julian Harrap was employed as architect and supervised the re- establishment of the house to what can be seen today. The principal room on the Northem side had the partitions removed but no other fundamental changes were made. A space was found for a kitchen on the ground floor, it no longer being appropriate for food to be prepared in the cellar and brought to table by dumb-waiter. Bathrooms were introduced in the upper two storeys and efficient central heating installed throughout the house, together making the house a pleasant residence whilst not losing the original concepts and architectural quality.

In several respects The Round House is an important building and it is surprising that it is not more widely known. The unusual oval shape and the ingenious plan make it an object of considerable interest in England where architectural oddities of this kind have seldom achieved concrete form on a large scale. In some of its features, particularly in the form of the roof, elements of Regency architecture make an early appearance, anticipating villas like Nash’s Cronkhill by a decade. If the design was indeed provided by John Plaw his stature as an architect is considerably increased.

From research by Neil Burton, architectural historian at the GLC, 1977.

Updated by Michael Heap, 1997.